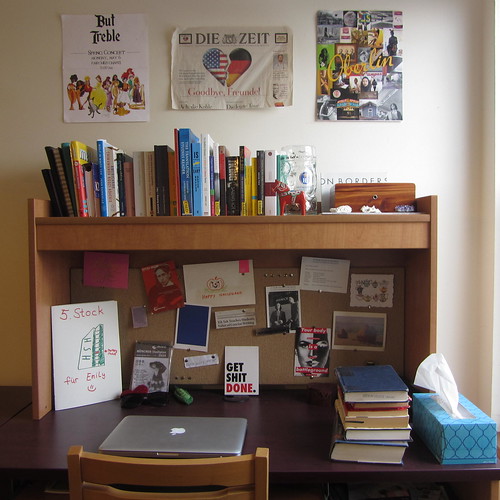

My Semester in Books, 2nd Edition

December 14, 2014

Emily Wilkerson ’15

Somehow it's happened, classes are over and all I have left to do is to plow through my finals. In the last few days all of my classes have had some sort of wrap-up. I've spent time thinking and talking about the over-arching themes and ideas in each of my courses, and in most cases, I've been reflecting on the things I read. Because of that I thought I'd do some reflecting here on the blogs and rather than doing my standard paragraph or two about each class, I decided to do another edition of My Semester in Books. Originally I had planned to write a brief blurb about every book I was assigned this semester as I did in the first post, but there were a few books that I realized I had a lot to say about, so I decided to just highlight the books that made a big impression on me, which ended up being about half of the books I read.1

A note on spoilers: I think there's a statute of limitations on spoilers, so if a book was released more than, say, 20-30 years ago I won't give a spoiler warning. Most of the books I talk about here can't really be spoiled. However, one or two of these books have major twists at the end and I think knowing them before you read would negatively affect the reading experience. In those cases I've taken care not to mention the twists in this post.

Housekeeping - Marilynne Robinson

Although she's a Pulitzer Prize winner I had never heard of Marilynne Robinson before taking this course. After reading Housekeeping, however, I want to read everything she's ever written. Housekeeping is about two sisters living in a small, Western town and their aunt who comes to take care of them after their mother dies. Almost every single character in the book is a woman, and one of the major questions in the novel is what does it mean to be a woman? Is a woman meant to keep house and make a home for herself and her family? Or can a woman be a wanderer, a transient? After a full year of thinking about what home means to me, these questions feel very relevant, but even if those questions don't seem to interesting to you, there is a lot to recommend this book. Robinson's writing style is so incredibly lovely. There's a sort of softness to it, you can go through paragraphs without quite knowing what's happening, but her sentences can also pack a real emotional punch. Overall Housekeeping is a powerful read and it has stuck with me in the months since I put it down.

The Handmaid's Tale - Margaret Atwood

I actually read this book the summer before last and loved it, so I was pleased to see that it was on the syllabus for Contemporary Literary Theory. The Handmaid's Tale is set in the Republic of Gildead, a totalitarian, theocratic state in the former US which severely restricts women's rights to the point that women aren't allowed to read, write, or hold paying jobs. The narrator is a Handmaid, which means that her prescribed role in society is to act as a surrogate mother for the barren wives of powerful men (the concept of sterility is forbidden in Gilead). In short, the world is dystopian and terrifying, and it was the world that I focused on during my first reading of the book. This time, though, the theoretical readings and our great in-class discussions led me to ask new questions of The Handmaid's Tale: How do language and non-linguistic signs (i.e. colors and symbols) relate to the construction of the self? What is the relationship between language and pleasure? And what does it mean to be free?

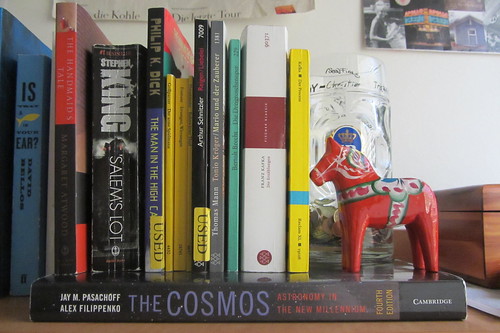

The Man in the High Castle - Philip K. Dick

This book could also be described as a dystopian novel - it's set in an alternate US circa 1962 in which the Axis Powers have won World War II and Japan and Germany jointly occupy the country and most of the world - but whether or not you choose to describe it that way betrays a lot about what you think a dystopia looks like. Well, that's not entirely true. Dick makes it clear that the German-occupied areas are pretty damn dystopian, but there's a bit of a gray area in the Japanese-occupied zone, called the Pacific States of America, where all but one of the multiple narrators live or at least spend most of the story. In the PSA the governing class is exclusively Japanese, and non-Japanese Americans have no real opportunities for advancement, agency, or independence. As one person in my class said, the experience of White Americans in the PSA is remarkably similar to the experience of POC in the US, and if we want to call the PSA a dystopia, we have to acknowledge that the US is one as well.

Woyzeck - Georg Büchner

I don't have a bound copy of Woyzeck (the bookstore ran out and my professor was awesome enough to make a photocopy for me), but I would be remiss if I didn't mention it here because it's a pretty extraordinary play. It was written about 200 years ago, the author got typhus and died before he could finish writing it, and its subject is a poor and arguably insane man who (probably) murders the mother of his child - and yet it's one of the most popular plays in the German repertoire today.2 Another amazing thing about this play is that it seems to articulate some of the concerns of Marxism even though it was written in 1836-37 and The Communist Manifesto wasn't published until 1848. A point of particular interest for me was that this was the first of many books I read this semester that explored the relationship between the mental and physical health of an individual and the demands placed on the individual by the society they live in.

Reigen (La Ronde) - Arthur Schnitzler

It's a tough call, but Reigen might be my favorite thing I read for my Intro to German Lit class. For one, I find the structure intriguing. Each of the 10 scenes features a woman and a man talking before and after having sex somewhere in Vienna in the 1890s. There are 10 characters who cycle through the scenes, so that each one is featured in two successive scenes, with the exception of the whore, who is in the beginning and ending scenes. Because the characters come from different social classes, ranging from the aforementioned whore to a Count, Schnitzler is able to explore a wide variety of power dynamics and how those power dynamics play out in sexual relationships. If you're thinking that this play sounds pretty heteronormative you are right, it absolutely is, but it was also pretty progressive for its time. In fact, it was so scandalous in turn of the century Vienna that it was banned after its original 1900 publication and it wasn't performed until 1920.

Die Erzählungen (Stories) - Franz Kafka

This book was actually on the syllabus for both of my German classes. In intro to German lit we were assigned to read "Die Verwandlung" ("The Metamorphosis") and in my Kafka class we read a bunch more stories, my favorite of which was "In der Strafkolonie" or "In the Penal Colony." Some people say that what you get out of a story by Kafka says more about you than it does about Kafka. I think that's true of most, if not all, literary fiction, but I do have to hand it to Kafka, he's able to write about an unbelievable variety of topics in very few pages. For example, "In der Strafkolonie" would be the great starting place for a conversation about colonialism, corrupt legal systems or legal systems more generally, faith and religion, torture, the connection between pain and mysticism, machines, the relationship between the bodily and the textual, what it means to be just, etc., even though it's only 31 pages in length.

Der Process (The Trial) - Franz Kafka

Anyone who read my original Semester in Books post and remembers my feelings about The Castle will not be shocked to find out that I didn't really enjoy reading this book. Often as I paused in between paragraphs I'd notice that my shoulders had tensed up or that I'd developed a headache. In fact, I even wrote one of my weekly reaction papers on how and why Kafka creates anxiety in Der Process. That being said, Der Process was the topic of a lot of interesting discussions and has certainly given me a lot to think about. While reading it this particular semester, it was difficult not to think about the many failings of the particular criminal justice system I live under. Der Process begins with the main character, Josef K., being accused of an unknown, unnamed crime and arrested. For the rest of the book he is, more or less, on trial. He tries to defend himself and seeks help from a variety of sources, but not having any idea how the court works, he has no chance of escaping conviction. At the end of the book, he is finally executed, "like a dog!"

The parallels between Der Process and the recent violence against black bodies aren't perfect, but they were impossible for me to ignore. Throughout the book, Josef K and the other accused men fail to understand how the court functions, namely that it functions only to convict the "guilty" and keep the powerful in positions of power. Their lack of understanding frustrated me as I read, it seemed unrealistic, but after seeing courts fail to indict Daniel Pantaleo and Darren Wilson for the murders of Eric Garner and Mike Brown, I have seen how unwilling people are to understand something that threatens their worldview, even if it's the most obvious thing in the world. Josef K's fruitless search to find someone, anyone who was to help him was tough to read because, as these events unfolded, it started to seem more and more realistic. No one can help him because everyone is "just doing their job" and no one has any real power to change the legal system as a whole. And can Josef K. escape that system somehow? No, because something in his face, something in way he holds his lips marks him as one of the accused, one of the guilty, which in turn marks him for death.

On the last day of my literary theory class, Pat Day quoted Walter Benjamin's On the Concept of History, "there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism." He explained that this assertion means that not only are these two seemingly contradictory ideas not contradictory at all, but that they allow for each other's existence. So it is with law and lawlessness. In every civilization, every lawful society there are elements of the barbaric and the lawless. In every act of barbarism or lawlessness, there is awareness of the civilized, of the legal. So it is in the world, so it is in Oberlin, and so it is in the books I read this semester.

Footnotes

1I also read a LOT of things that weren't books this semester (shoutout to Blackboard!). If you'e interested in hearing about the theoretical texts, poems, individual short stories, or pieces of secondary literature I read for any of my classes, just ask, but some of my favorite non-book assigned readings were poems by Annette von Droster-Hülshoff and Elsa Lasker-Schüler, short stories by Shalom Auslander, "The Laugh of the Medusa" by Hélène Cixous (women in my life - PLEASE READ THIS ESSAY), "Crisis in Orientalism" by Edward Said, and excepts from Frederic Jameson's The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.

2If you're an opera buff or lover of 20th century classical music, you've probably heard of Alban Berg's Wozzeck, which he was inspired to write after attending the first production of Woyzeck in 1914.

Similar Blog Entries

A Term of Trying New Things

December 11, 2024

An Ode to Obsession: Some unexpected academic loves I found this semester

November 30, 2024

Creative Writing Workshops

November 21, 2024